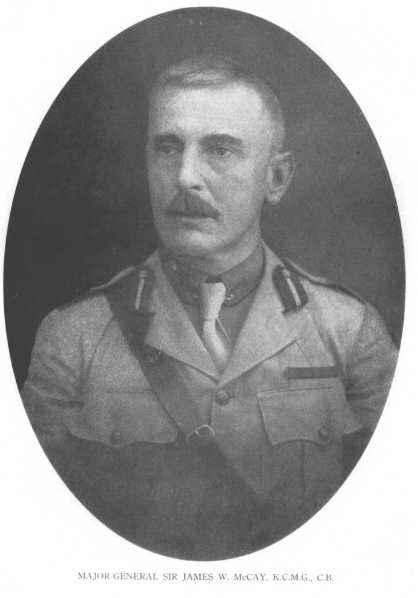

Photograph from History of Scotch College, Melbourne,

1851-1925, p. 385

James Whiteside (Jim) McCay was born in Ballynure, Antrim, Ireland on 21 December 1864, the eldest of ten children of a Presbyterian minister, who migrated to Australia in 1865. A formidable intellect, he was educated at Castlemaine State before he won a scholarship at age 12 to Scotch College where he was dux of the school in 1880. He entered Ormond College at the University of Melbourne, where he was awarded a Bachelor of Arts (BA) in 1892 and a Master of Arts (MA) in 1894, majoring in Mathematics. Then in 1897, he obtained a Master of Law (LLM) degree with first class honours.

To support himself, McCay worked as a teacher at Toorak College. He purchased Castlemaine Grammar in 1885. As principal, he was a firm disciplinarian, and a strong supporter of higher education for women. After completing him law degree, he began to practice as a solicitor.

McCay was active in politics. He was a member of the Castlemaine Borough Council from 1890 to 1893, and then of the Victorian Parliament from 1895 to 1900. McCay worked for Federation and won the seat of Corinella as a Protectionist in the first Federal parliament in March 1901 and was re-elected unopposed in 1903. He went on to serve as Defence Minister from 18 August 1904 to 5 July 1905. Although his term in office was brief due to the political instability of the time, McCay was involved in a number of important reforms, including the establishment of the Military Board. His electorate was abolished in 1906 and his effort to win the seat of Corio was unsuccessful. He ran for the Senate in 1910 but was again defeated.

Commissioned into the Victorian Rifles in 1884, McCay rose to command the of the 8th Regiment in 1900. On 6 December 1907 he was appointed to command the new Australian Intelligence Corps with the rank of full colonel. In this capacity he advanced the career of his old schoolmate, John Monash. After conflict with the Military Board, his appointment was terminated on 31 March 1913.

On 3 August 1914 McCay was appointed Deputy Chief Censor. This appointment lasted only two weeks before he was appointed to command the 2nd Infantry Brigade on 15 August 1914 and handed over the censorship post to John Monash. At a function in his honour, McCay surprised many by asserting that the war would be long and hard.

In training his command, McCay showed conspicuous ability. He did much of the detail work himself , drew up his own orders and sometimes even involved himself with training his platoons. He demanded and received a high standard from his men.

This paid off on 25 April 1915, when his brigade was subjected to rapid changes or orders and a chaotic situation. McCay showed his forceful character and occasional ruthlessness in directing the fighting on the 400 Plateau. Arriving around 6am, McCay accepted MacLagan's directives, even though MacLagan was his junior and it represented a complete change of plan. In those early hours, McCay was shot twice through the cap and once through the sleeve.

At 4:45 pm , McCay telephoned division headquarters with an urgent request for reinforcements. Lieutenant Colonel C. B. B. White, the chief of staff, answered, and explained that division had only one battalion (the 4th) left. McCay explained his situation, and Major T. A. Blamey, of division headquarters, added his opinion to McCay's. Bridges then came on the line and said: "I want you to speak to me not as subordinate to general, but as McCay to Bridges. I have only one battalion left. Do you assure me that your need is absolute?" McCay replied that it was, and the 4th Battalion moved into the gap on Bolton's Ridge.

On 29 April 1915, the 2nd Brigade was sent to reinforce the British at Helles. Ordered to send his strongest brigade to Helles, Bridges chose the 2nd, his second strongest, owing to his confidence in McCay. At Second Krithia, McCay found himself ordered to make a daylight advance across open ground at extremely short notice. He complied and, showing great personal courage, drove his men forward, forcefully directing the attack from the front. McCay was perhaps unfairly blamed for the heavy casualties incurred in the needless attack, in which he was wounded in the leg. In the attack, his brigade suffered 1,000 casualties for an advance that could have been made without cost after dark.

McCay returned to the front at Anzac on 8 June 1915, before his leg had fully healed. The GOC AIF, Major General J. G. Legge, designated McCay to command the 2nd Division, which had begun forming in Egypt, but on 11 July 1915, the day before he was to leave to take up his new post, McCay's leg gave way. He was evacuated to Malta, where the surgeons operated, and then was invalided back to Australia.

McCay arrived back in Australia on 11 November 1915 to a hero's welcome. There he was appointed Inspector General on 29 November 1915, with the rank of Major General. As such, he began the training of the new 3rd Division, which he was designated to command. Because of the Australian governments insistence on its divisions in Egypt being commanded by Australian officers, McCay returned to Egypt to take command of the newly formed 5th Division in March 1916, without having to face a medical board, which might well have failed him.

Arriving in Egypt on 21 March 1916, McCay found plans underway to have II Anzac Corps, of which his 5th Division was a part, march across the desert to relieve I Anzac Corps on the Suez Canal, I Anzac Corps being under orders to move to France. McCay protested the order but was overruled. In the march that followed, the men suffered terribly, especially in the 14th Infantry Brigade, where there was considerable straggling. McCay judged the arrangements of the brigade's commander, Brigadier General G. G. H. Irving, to be faulty, and relieved him of his command. But some blamed McCay for his part in the debacle.

Although the last division to sail from Egypt in June 1916, the 5th Division was the first to be committed to action, at Fromelles in July 1916. Once again McCay found himself as part of an ill-planned and ill-advised attack. Most of the responsibility for this, the most costly 24 hour period in Australian history, lay with the British Corps commander, Lieutenant General Sir Richard Haking, but others, including McCay, have to share some of the blame. In the wake of the battle, McCay's unpopularity with his men was heightened not just by the shattering defeat, but by his refusal to call a truce with the enemy to collect the wounded. His relationships with his subordinates also declined when he sacked Brigadier General H. Pope for getting drunk after the attack, although Pope was probably only exhausted.

In January 1917, McCay was relieved of his command, ostensibly on the grounds of ill health, particularly his lameness, but a deterioration of his relationship with his corps commander, Lieutenant General W. R. Birdwood, may have had as much to do with it. On 1 May 1917, McCay was appointed to command the AIF Depots in the UK, an appointment made over the head of Birdwood by the Australian government on the advice of Brigadier General R. M. McC. Anderson.

McCay spent the rest of the war in the UK, efficiently and loyally training reinforcements. He counselled the Australian government against the 1917 conscription referendum on the grounds that the conscripts could not arrive at the front before 1919. In 1918, McCay pared the training establishment to the bone in order to free up the maximum number of men for service at the front. Aware of the government's desire for an Australian corps commander, he attempted to persuade Birdwood to resign the corps command in his favour. Failing that, he attempted to gain obtain command of the 3rd Division when Monash was elevated to the post. Birdwood turned him down on both requests.

In January 1920, McCay, along with Legge, Monash, Hobbs and White, was appointed to a committee chaired by Chauvel, to examine the future structure of the army. In recognition for his wartime service, McCay was made a Knight Commander of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in 1918, and a Knight of the British Empire (KBE) in 1919. He retired from the army with the rank of lieutenant general in 1926.

McCay did not resume his legal practice. Instead, he became a business advisor to the Commonwealth Government until 1922. He headed a Victorian 1919 Royal Commission into Fair Prices. Afterwards, he became Deputy Chairman of the State Saving Bank of Victoria.

In his later years he was in constant pain from his war wound. He died on 1 October 1930, and was buried at Box Hill Cemetery.

It was McCay's great misfortune to be constantly thrust into situations where his courage, his forcefulness and his drive were at times more of a liability than an asset. In another time and place, these qualities, plus his intellect, might have made him great. As it was, McCay's achievements were as a trainer of troops and a patron of the careers of others. Above all, McCay was lacking in that most elusive attribute of a great general: luck.

Sources: C. E. W. Bean, The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. Volume I: The Story of Anzac, pp. 400-401; Wray, Christopher, Sir James Whiteside McCay

Page created by Ross

Mallett

ross@metva.com.au

Last update 8 June 2010