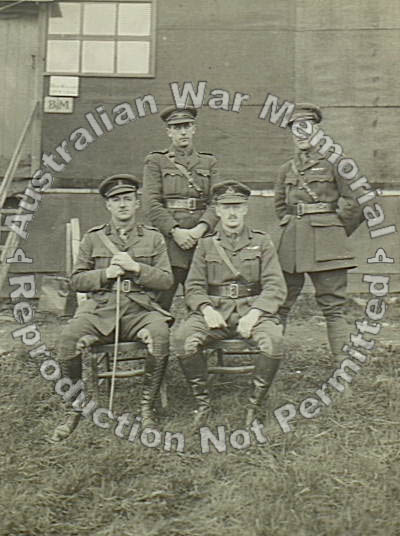

AWM Negative Number: E01769 Caption: Neuve Eglise; 24 Feb 1918; Informal portrait of the Staff Officers of the 3rd Brigade.

Left to right, back: Captain R. R. Agnew, Assistant Brigade Major; Lieutenant R. F. Stanistreet MC MM,

Signal Officer.

Front: Major H. W. Hutchin, Brigade Major; Brigadier General H. Bennett CB CMG, Companion.

Unknown photographer

Henry Gordon Bennett was born in Balwyn, Melbourne on 16 April 1887, the second child of George Jesse Bennett, a schoolmaster. Gordon was educated at Balwyn State and Hawthorn College, and joined Australian Mutual Provident (AMP) as an actuarial clerk.

Bennett was commissioned in the 5th Infantry as a second lieutenant on 14 August 1908. He was rapidly promoted to lieutenant in 1909 and major on 1 July 1912. When war broke out in 1914, he was serving as a major in the 64th (City of Melbourne) Battalion.

Bennet joined the AIF on 19 August 1914 as second in command of the 6th Battalion. The original commander of this unit, Lieutenant Colonel J. M. Semmens was considered too delicate for frontline service, and was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel W. R. McNicoll, an officer ten years older than Bennett but still six months Bennett's junior in grade.

It was as such that he landed at Anzac on 25 April 1915. Bennett took the first two companies of the battalion to the spurs on the south of the Lone Pine plateau. From there, they attempted to advance on Pine Ridge through the thick scrub. When some men suggested that the plan had miscarried and that they should they retire, Bennett told them that he would lead them -- forward. This he did, taking up positions on Pine Ridge. Around 4pm he was wounded, shot in the wrist and shoulder, while directing fire on the Turkish positions. Bennett was evacuated to a hospital ship but jumped ship and rejoined his battalion in the front line the next day.

Bennett's courage and leadership came to the fore at the Second Battle of Krithia on 8 May 1915. Ordered by Brigadier General J. W. McCay to advance towards the Turkish positions in broad daylight, Bennett led his men forward under heavy fire, first at a steady walk, then by rushes. Men were hit all around him, including McNicoll but Bennett miraculously remained unscathed, apparently unable to be killed by conventional means. Bennett dug in with about twenty men at the furthest point reached by the advance. He became commander of the battalion the next day, the only original officer of the 6th Battalion left standing.

On 7 August 1915, Bennett and the 6th Battalion were ordered to capture the German Officers' Trench. It was a dangerous and desperate operation, but a necessary one, because machine guns at German Officers' enfiladed the positions at Russell's Top, Pope's Hill and Quinn's Post. As a result of the trenches and tunnels through which the advance was to begin being filled with debris by mine explosions, the attack became disorganised and was halted by the Turks. Ordered to try again by Major General H. B. Walker, who knew that the whole campaign plan required the capture of the position, Bennett and the 2nd Brigade's Brigade Major, Major C. H. Jess, reorganised the troops and made a second attempt. It too failed. Walker then ordered a third attempt which Bennett resolved to lead in person. However, Brigadier General J. K. Forsyth and Major D. J. Glasfurd managed to prevail upon Walker to cancel the attack.

For his services at Gallipoli, Bennett was twice mentioned in dispatches and was made a Companion of St Michael and St George (CMG).

In France, Bennett continued to add to the reputation that he had won at Gallipoli. At Pozieres, Bennett located his headquarters in a log hut that was struck by shells six times but was saved by the debris that had fallen on it. Bennett feared for his men, who were being mercilessly shelled in one of the most ferocious bombardments of the war, in which they were constantly being buried and soldiers were being driven mad. Somehow they managed to hold on. A few weeks later, while supervising a trench raid by the 8th Battalion one night, Bennett noticed that the patrol had returned without their lieutenant. Taking his runner with him, he immediately went out into No Man's Land in search of the missing officer. He found him, wounded and tangled in the wire, and brought him back. The wounded officer, Lieutenant W. D. Joynt, made a full recovery and later won the Victoria Cross.

On 3 December 1916, Bennett took over command of the 3rd Infantry Brigade and was promoted to colonel and temporary brigadier general. At 29, he became the youngest ever general in the Australian army. He led the brigade for the rest of the war, participating in the Advance to the Hindenburg Line (March 1917), Second Bullecourt (May 1917), Menin Road (September 1917), the Lys (April 1918), Amiens (August 1918) and the Hindenburg Line (September 1918). For his services France, Bennett was mentioned in dispatches six more times and was made a Companion of the Bath (CB) in 1918.

After the war, Bennett worked as a clothing manufacturer and a chartered accountant. He became chairman of the New South Wales State Repatriation Board in 1922. In October 1928, he became one of the three commissioners administering the City of Sydney. He was head of the New South Wales Chamber of Manufacturers from 1931 to 1933 and Australian Chamber of Manufacturers from 1933 to 1934.

Bennett commanded the 9th Infantry Brigade from 1921 to 1926 and then the 2nd Division from 1926 to 1932. He was promoted to major general on 1 August 1930. In 1937, Bennett published a series of articles in the Sydney Sunday Sun, strongly criticising the nation's and the army's lack of preparedness for another major war and the agenda of regular officers to reserve senior commands for themselves. Eventually the Military Board asked Bennett to discontinue the series. No action was taken against Bennett but he had become a controversial figure.

When war broke out in 1939 Bennett was the senior general on the active list and at 52, still young enough for an active command. But he was passed over for command of the AIF in favour of Major General T. A. Blamey. As new divisions were formed, Bennett was passed over again and again, although he was given charge of the Eastern Command Training Depot and like a number of Great War generals, given a command in the Volunteer Defence Corps, the Australian version of "Dad's Army". The Chief of the General Staff, General Sir C. B. B. White, when pressed, informed Bennett that he had "certain qualities and certain disqualities" for an active command.

The death of White in a plane crash, however, gave Bennett his chance. White was replaced by Lieutenant General V. A. H. Sturdee, the commander of the 8th Division, who felt that Bennett was qualified as his replacement, and that his antipathy towards regular officers had died down. The 8th Division began to move to Malaya in February 1941 and Bennett moved there with his advanced headquarters on 4 February. A frustrating period followed, for his command was low on the global priority list. Bennett would be appointed GOC AIF Malaya, but only two brigades of his division were sent to Malaya. The remaining brigade was spread out across the islands to the north of Australia. Bennett's relations with his British superior, Lieutenant General E. A. Percival, were not be good, for Bennett never hesitated to openly criticise the British whenever he felt that it was warranted. In any event, Bennett would be the least of Percival's problems.

On 8 December 1941, the Japanese landed in Malaya and soon gained the upper hand. Despite some local successes, such as at Gemas on 14 January 1942, Bennett and his men faired little better than the British soldiers they derided. The whole army was forced to withdraw to Singapore by the end of the month. On 8 January 1942 the Japanese landed on Singapore Island, driving the Australians back towards the city. On 15 February 1941, Percival surrendered to Lieutenant General T. Yamashita. The fall of Singapore was one of the greatest disasters in Australian history.

Bennett elected not to surrender. He ordered his men issued with new clothing and two days' rations, and handed over command of the 8th Division to Brigadier C. A. Callaghan. With his aide, Lieutenant G. H. Walker and a staff officer, Major C. J. A. Moses, and some planters serving with the volunteer forces in Malaya, Bennett commandeered a sampan at gunpoint and slipped away from Singapore at 1am. In this they made the dangerous trip across the Malacca Straight to the east coast of Sumatra, where they transferred to a harbour launch, the Tern, in which they sailed up Sumatra's Djambi River. They were about to set off on the next stage of their journey when Bennett heard that help was urgently needed by a group of wounded women and children stranded on Singkep Island. A Dutch doctor had procured a launch, the Heather, but had no one to operate its diesel engine. Bennett asked for volunteers from the crew of the Tern and three men stepped forward. Heather duly made the trip and the three men eventually reached India.

Meanwhile the three intrepid Australians reached Padang, on the west coast of Sumatra. From there they flew to Java, from whence Bennett went ahead of them on a Qantas plane to Australia, arriving in Melbourne on 2 March 1942. It is estimated that some 3,000 people escaped from Singapore. Thousands of others were not so lucky; they were killed by bombs or bullets, drowned, shipwrecked or, like the nurses of the 2/13 General Hospital, murdered by the Japanese.The response to Bennett's escape was mixed. Many senior officers, including Sturdee, felt that Bennett had deserted his men. But Prime Minister John Curtin issued a statement that read:

I desire to inform the nation that we are proud to pay tribute to the efficiency, gallantry and devotion of our forces throughout the struggle. We have expressed to Major General Bennett our confidence in him. His leadership and conduct were in complete conformity with his duty to the men under his command and to his country. He remained with his men until the end, completed all formalities in connection with the surrender, and then took the opportunity and risk of escaping.

While Bennett may not have had many answers to the Japanese tactics, he did compile notes on the subject, and eventually published an entire manual that was circulated with the Australian Army at large.

On 7 April 1942, Bennett was promoted to lieutenant general and given command of III Corps in Perth, responsible for guarding Western Australia. Initially this was a key post but it gradually became a backwater. On being informed by General T. A. Blamey that his chances of another active command were slim, a bitterly disappointed Bennett transferred to the Reserve of Officers on 9 May 1944.

Bennett published his own account of the campaign in Malaya later in the year in his book Why Singapore Fell. When the war ended, Percival, released from captivity, sent a letter to Blamey accusing Bennett of relinquishing his command without permission. Instead of just tearing it up, Blamey convened a court of enquiry under Major General V. P. H. Stanke, who found that Bennett was not justified in handing over his command, or in leaving Singapore. A storm of protest erupted from men of the 8th Division, who saw their own performance on trial as well, so on 17 November 1945, Prime Minister J. B. Chifley appointed a Royal Commission under Justice G. Ligertwood to report on the circumstances surrounding Bennett's escape. The commissioner concluded that Bennett had not been a prisoner of war at the time and was under orders to surrender. Very few legal or military experts would agree with this conclusion.

Bennett became an orchardist at Glenorie, near Sydney, until 1955. He wrote a number of articles on military topics and continued to publicly defend his actions. He died on 1 August 1962 and was cremated.

Bennett's World War I career has been completely overshadowed by he events of the first weeks of the Pacific war. But his courage should not be forgotten.

Sources: Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1940-1980, pp.164-165; AWM 183/7; Bean, C. E. W., The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. Volume I: The Story of Anzac pp.133, 382, 411-420; Volume II: The Story of Anzac pp. 31-32, 41, 602-606; Volume III: The AIF In France 1916, pp. 589-590; Joynt, W.D., Breaking the Road for the Rest, pp. 97-104, 188-190; Wigmore, The Japanese Thrust, pp. 30-35, 381-388, 650-652

Page created by Ross

Mallett

ross@metva.com.au

Last update 18 August 2002